When it comes to powering mobile robots, batteries present a problematic incongruity the further energy they contain, the further they weigh, and therefore the more energy the robot needs to move. Energy harvesters, like solar panels, might work for some operations, but they don’t deliver power snappily or constantly enough for sustained trip.

James Pikul, assistant professor in Penn Engineering’s Department of Mechanical Engineering and Applied Mechanics, is developing robot- powering technology that has the stylish of both worlds. His environmentally controlled voltage source, or ECVS, works like a battery, in that the energy is produced by constantly breaking and forming chemical bonds, but it escapes the weight incongruity by chancing those chemical bonds in the robot’s terrain, like a harvester. While in contact with a essence face, an ECVS unit catalyzes an oxidation response with the girding air, powering the robot with the freed electrons.

Pikul’s approach was inspired by how creatures power themselves through rustling for chemical bonds in the form of food. And like a simple organism, these ECVS- powered robots are now able of searching for their own food sources despite lacking a “ brain. ”

In a new study published as an Editor’s Choice composition in Advanced Intelligent Systems, Pikul, along with lab members Min Wang and Yue Gao, demonstrate a wheeled robot that can navigate its terrain without a computer. By having the left and right bus of the robot powered by different ECVS units, they show a rudimentary form of navigation and rustling, where the robot will automatically steer toward metallic shells it can “ eat. ”

Their study also outlines more complicated geste that can be achieved without a central processor. With different spatial and successional arrangements of ECVS units, a robot can perform a variety of logical operations grounded on the presence or absence of its food source.

“ Bacteria are suitable to autonomously navigate toward nutrients through a process called chemotaxis, where they smell and respond to changes in chemical attention, ” Pikul says. “ Small robots have analogous constraints to microorganisms, since they ca n’t carry big batteries or complicated computers, so we wanted to explore how our ECVS technology could replicate that kind of geste . ”

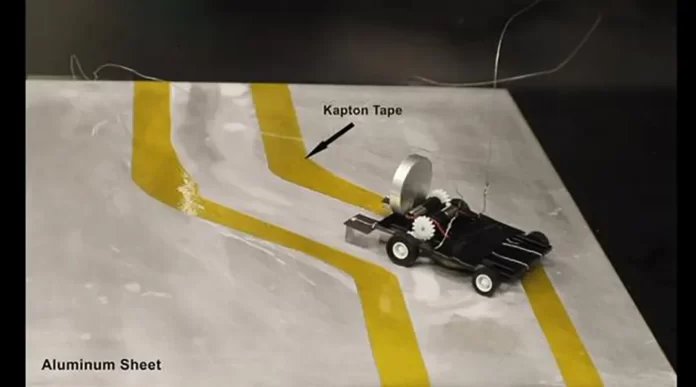

In the experimenters ’ trials, they placed their robot on aluminum shells able of powering its ECVS units. By adding “ hazards ” that would help the robot from making contact with the essence, they showed how ECVS units could both get the robot moving and navigate it toward further energy–rich sources.

“ In some ways, ” Pikul said, “ they are like a lingo in that they both sense and help digest energy. ”

One type of hazard was a curling path of separating tape recording. The experimenters showed that the robot would autonomously follow the essence lane in between two lines of tape recording if its EVCS units were wired to the bus on the contrary side. However, for illustration, the ECVS on the right side of the robot would begin to lose power first, If the lane twisted to the left wing.

Another hazard took the form of a thick separating gel, which the robot could gradationally wipe down by driving over it. Since the consistence of the gel was directly related to the quantum of power the robot’s ECVS units could draw from the essence underneath it, the experimenters were suitable to show that the robot’s turning compass was responsive to that kind of environmental signal.

By understanding the types of cues ECVS units can pick up, the experimenters can concoct different ways of incorporating them into the design of a robot in order to achieve the asked type of navigation.

“ Wiring the ECVS units to contrary motors allows the robot to avoid the shells they do n’t like, ” said Pikul. “ But when the ECVS units are in resemblant to both motors, they operate like an ‘ OR ’ gate, in that they ignore chemical or physical changes that do under just one power source ”

“ We can use this kind of wiring to match natural preferences, ” he said. “ It’s important to be suitable to tell the difference between surroundings that are dangerous and need to be avoided, and bones that are just inconvenient and can be passed through if necessary. ”

As ECVS technology evolves, they can be used to program indeed more complicated and responsive actions in independent, computer less robots. By matching the ECVS design to the terrain that a robot needs to operate in, Pikul envisions bitsy robots that crawl through debris or other dangerous surroundings, getting detectors to critical locales while conserving themselves.

Still, we can have robots that avoid shells that are dangerous, but power through bones that stand in the way of an ideal, “ If we’ve different ECVS that are tuned to different chemistries.